By Quoc-Tan Tran

In October 2020, I was fortunate to accomplish my third secondment at the Museum of European Cultures (MEK) – National Museums in Berlin. Around that time, Germany had loosened Covid restrictions, and the University of Hamburg had allowed staff to retake business trips. That was my last secondment within POEM and the one I had longed for, because I always wanted to do fieldwork in an ethnographic museum. I said “I was fortunate” because right after I finished my trip and returned to Hamburg in November, the restrictions were in place again. Museums had to close their doors, many exhibitions and workshops were postponed, and lots of museum staff are subject to unstable employment.

That is to describe how fortunate I am — to do fieldwork and wander about in physical sites, to talk face-to-face with museum staff, to see framed paintings stored in racks and inspect real index cards in old multi-drawer cabinets. In short, I was able to observe what craftwork means in a museum context, the manner it is arranged and assembled, and how it tells cultural heritage field-workers interesting stories about the vital role of “invisible work”.

“Invisible work” that supports the infrastructure

What often comes to our mind when we ask ourselves “What is an infrastructure?” is an image of the material base or foundation upon which a collective action of a collective body operates. In everyday language, an infrastructure for museum inventory could mean a storage room for paintings, with each content unit divided by rack or shelf and classified by labels. Or, an infrastructure for organic farming could mean a greenhouse structure with transparent walls and roof; it also includes the soil on which plants — let’s say tomato — grow. However, infrastructure studies scholars have shown that these metaphors are not accurate to describe the multi-layer relationship between everyday practices and everyday tools and technology.

The American sociologist Susan Leigh Star suggested that we should ask the question “When is the infrastructure?” rather than “What is?” She used the classic example of the water system[1] in a household to illustrate the moments when those walls, roofs, storage rooms, racks, shelves and labels become invisible, or are hidden from our eyes. We see the water running when we turn on the tap; however, as Star pointed out, we never see how things work underneath the tap. We have access to clean water and use it as something essential to our everyday life, but we don’t know how complicated it is to transport that safe water to the tip of the tap: Has the water been running through any softening system? Which tools and treatment cover water purification or pumping or wastewater management? All that invisible work, invisible inside the network of pipes, becomes the infrastructure itself when we ask right questions at the right moment. When the tap has slight hiccups, we know that something underneath it doesn’t function correctly. That gives us an idea of invisible work: the work that supports the smooth functioning of infrastructure, and needs to be handled with care.

Invisible work or neglected things?

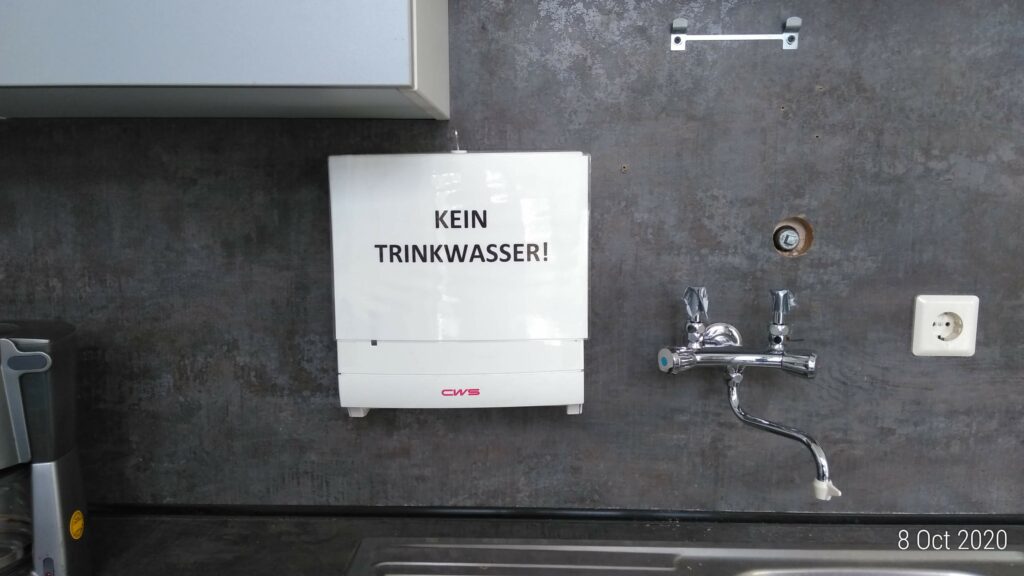

On the first day at the MEK, I witnessed something unusual in the common kitchen space for staff: There was no drinking water. Susanne (my POEM colleague at the MEK) told me that in order to make coffee she needed to go downstairs to get drinking water, then go upstairs to get the coffee and boil the water, and after finishing she had to go downstairs again to put the used cups in the dishwasher. Another problem, intertwined with the drinking water issue, was that the toilet on the second floor (where almost everyone’s offices were based) wasn’t working because of the ongoing construction work. To use the toilet, staff had to go through the library, get to the staircase, then go downstairs to the foyer of the old exhibition space to go to the restroom on the ground floor. Still, the construction work was perceived as necessary and worth the double-staircase effort because it was about re-installing the pipes so that everybody would have access to drinking water from their working floor.

Figure 1. The sign “no drinking water” in the shared kitchen space at the MEK

Normally, you turn on the tap for a drink of water without thinking much about what is flowing behind the wall and the mechanism that is responsible for water supply. And now you realise that the hidden parts of this structure become more visible when something is broken. This reminds me of two things. First, infrastructure becomes visible upon breakdown, as Star and Ruhleder suggested, and we must study it in relation to organised practices. It’s important to remember, not only in the moments of failure, that the tap in the kitchen area offers a vital source of drinking water for staff; without it functioning smoothly, their everyday routines and everyday practices are all affected.

Secondly, this small troubleshooting moment reminds me that taking care is collaborative, and to perform responsibly the work practices requires a high degree of care. By “care” I mean the everyday doings that staff need to carry out to avoid any detriment to the museum objects or the functioning of the institution. In the next part, I will take one example — a case of documentation work at the Museum of European Cultures, or MEK — to elaborate further this second point: the collaborative aspect that affects the efficacy of care is not only evident in physical infrastructure (you remember “walls, roof, storage rooms, racks, shelves and labels” that I mentioned above 😉), but also in the digital part of organised work practices.

Care is collaborative: A case of museum documentation

During the one-month secondment, one part of findings that has a significant impact on my view of marginalised groups and marginalisation is about the information and documentation work at the MEK. I had talked to several system managers, who were responsible for the transition from the old Windows-based MuseumPlus Classic to the web and cloud-based MuseumPlus RIA[2]. The data migration causes many troubles for staff — themselves being curators and museologists while having “extra” caring task of overseeing the data transfer from the old to the new system and, together with it, checking the consistency of the whole bunch of input data. The MEK is a medium-sized museum, but they hold so many objects: about 285,000 in total, and only 130,000 being catalogued in the old system.

However, the arising problem is not about the systems themselves — the new RIA version is suitable for importing large databases and compatible with the old one. Rather, it lies in the MEK’s complex collections history[3] and the robust structure of the National Museums in Berlin (Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, or SMB)[4] where the MEK belongs. In fact, the SMB consists of 17 museums and 4 research institutes, and all the museum members are using the same documentation system but sometimes input data into corresponding fields in slightly different manners.

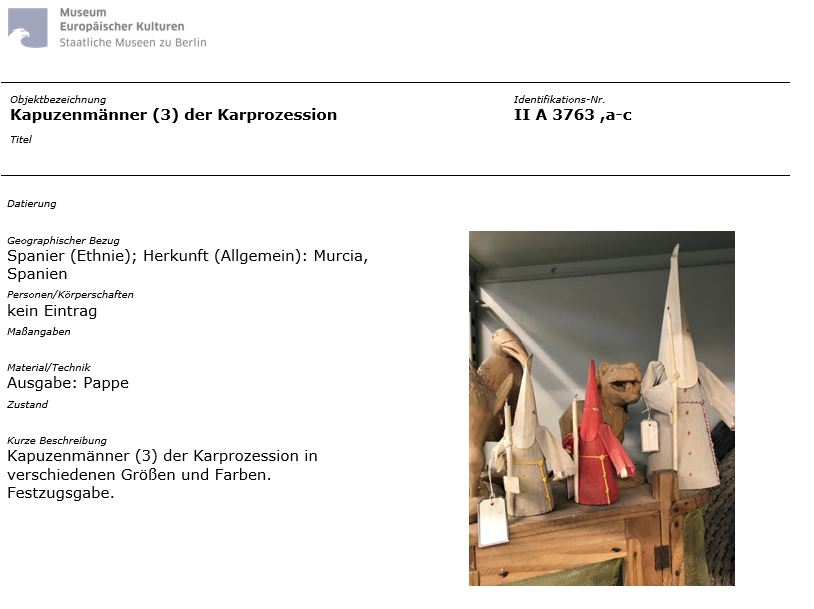

Figure 2. The catalogue entry of the object “II A 3763 ,a-c” in the MEK’s museum documentation system

This is the digital catalogue of one object whose photos had been just taken during the week I was working in the museum (late October 2020). A curator found this object in the museum’s basement and thought it could be useful for their upcoming exhibition on the Spanish region and city of Murcia. They only found it by accident because the keywords “Murcia” was indicated in the geographical information field. However, when the staff looked for this object’s catalogue entry in the digital system, they couldn’t find any information about from where the object exactly came. The “geographical reference” field only mentions Spanier (Ethnie), which is inaccurate in any level because you can’t say “Spanish (Ethnic)” as a geographical reference.

Is there any other information that gives us some hints? The “short description” field indicates Kapuzenmänner, which are men with high hoods in different sizes and colours [in verschiedenen Größen und Farben]. Karwoche mean “Holy week”, so Karprozession refers to the public march which takes place during the last week of Lent, the week immediately before Easter. The sole input data of “Karprozession” didn’t help much, or even at all, the staff who took care of the object. This lack of basic information was accidentally found and shouldn’t be applied to all 130,000 objects in the museum’s documentation system, but we can grasp an idea why the invisible work of documenting objects and maintaining data consistency is so important. That simply-put caring task would have required not only a great deal of physical work, but also a high degree of specialised knowledge concerning cataloguing and art-object classification.

How could “neglected things” earn an opportunity?

The object labelled “II A 3763 ,a-c” was not destined to be neglected. At some point where my fieldwork is concerned, the staff found this object and thought it would be interesting, and then they started taking care of it: take photos in multiple angles, improve the catalogue entry and make connections with other related objects. It may appear in their upcoming exhibition. It was just fortunate to be located in the right place at the right time, i.e. in the position or place to take advantage or earn an opportunity.

The image of the MEK suddenly came to my mind. With a little above 20 staff members, the MEK is not a small museum, but not a big one either. While the adjacent museums (Asian Art Museum and Ethnological Museum) have been moved to a more city-centre and showcase-ish location, which is the €600 million, 183,000-square-foot Humboldt Forum, the MEK remains in the Dahlem village, a beautifully green area at the margin of Berlin. That reminds me of the sense of a “fringe” — something located at the edge, which isn’t really visible and whose voice and position could be downplayed.

However, that “fringe” position could become the MEK’s advantage. The Humboldt Forum — set to open in 2019 but only opened digitally (and partly) on the 16th December 2020, has been subject to different kinds of criticism: vast holdings of colonial-era artefacts, implicit colonial power relationships, and the absence of provenance research, to cite a few. The MEK’s leadership should not be involved in tackling these controversies; its exhibitions are not concerned by the delay in the Forum’s opening. Indeed, the museum’s “fringe” position is one important reason I thought the MEK could be a perfect fit for my research’s quest onto marginalised voices and hidden layers of narratives that come in various forms, and can be experienced in different manifestations.

This led me to think not about how we should treat neglected objects (the discussion on this is long-dated and far from over), but about the nature of our regard when we encounter something in the margin, which might make us feel “on edge”. Through this above example, I explain how the invisible work of documentation or, in a cliché phrasing, the work of “taking care of objects” shed another light on things that have been long neglected. I call this documentation work, to borrow Star’s term [5], the “fringe” between fields. It is that understanding of these fringes and nuances — things located at the edge, or in the boundaries between domains of knowledge — that the field workers need to quest. The appearance of the “fringes” could be subtle, its use is insecure and precarious, and the work on itself could be easily forgotten. All these aspects, nevertheless, offer valuable other layers of narratives. The “fringes” could be far from the centre but definitively not hard to reach. They are, and will be, affected by our actions.

[1] For more: Star, S. L. (1999). The Ethnography of Infrastructure. American behavioral scientist, 43(3), 377-391.

[2] Standing for “Rich Internet Architecture”, the RIA version allows for better integration of collections management with digital asset management and other systems via Web Services.

[3] See “The History of the MEK Collections” at https://www.smb.museum/fileadmin/website/Museen_und_Sammlungen/Museum_Europaeischer_Kulturen/02_Sammeln_und_Forschen/MEK_Sammlungskonzept_EN.pdf

[4] My Medium article describes this complicated hierarchical structure in more detailed. See https://qtantran.medium.com/knowledge-co-production-wiki-goes-mek-36ee99e3ab97

[5] Star discussed the trouble of indexing and classification activities, as the result of the fringes of language. See Star, S. L. (2002). Infrastructure and Ethnographic Practice: Working on the Fringes. Scandinavian Journal of Information Systems, 14(2), 107–122.