By Franziska Mucha

What can you do with a digitised object, an online collection or even multiple collections drawn together on a platform? Masses of data and metadata get produced in digitisation processes of memory institutions. One of the main drivers of this process is for institution missions to widen access to and interaction with cultural heritage in the context of research and education (Nauta et al., 2017; NEMO, 2020). As digital objects offer new possibilities for sharing, interpreting, and reusing cultural content, they seem to be a useful resource to support participatory engagement with cultural heritage collections (Kallinikos et al., 2010; Owens, 2013).

However, memory institutions do not yet know much about the users they are providing content for. In addition, the default presentation of digital objects follows in most cases the logic of collection management systems (Cameron & Mengler, 2009; Srinivasan et al., 2010). There is a gap in research on the needs of potential user groups, forms of knowledge exchange, and ways of reusing digital objects (Müller, 2019; Terras, 2015; Valeonti et al., 2019).

In my research, I am aiming to find out how digital collections can become a more useful resource for different user communities. I am exploring how digital objects could be used in new ways by institutions and potential users, to come to a more holistic picture of their meanings and possible applications.

How to explore new ways of using digital objects together?

To gain insights into new ways of meaning-making and reuse of digital objects, I am observing and testing co-creative processes which bring together cultural heritage objects, interested people, and digital technology.

Co-creation is a term used across different fields, such as design, where it has a long tradition in participatory design (Sanders & Stappers, 2008). But in the last 20 years it has also gained influence in participatory museum work and economic value-creation models (Prahalad & Ramaswamy, 2004; Simon, 2010). The aim of co-creation is to work on a topic collectively so that multiple perspectives become visible and tangible in a form of a public output. As Elizabeth Sanders and Pieter Jan Stappers have illustrated, inviting more people to join a creative process leads to a “fuzzy front end” (Sanders & Stappers, 2008, S. 6). For me, this fuzziness symbolises also that co-creative processes touch upon and negotiate ideas of sharing authority, responsibility and decision-making (Dahlgren & Hermes, 2015; Gesser et al., 2020; Sandell et al., 2016).

For my research, co-creative processes settings offer rich qualitative cases in which mixed groups from within and outside the cultural heritage sector explore, share and discuss meanings and knowledge of digital objects.

Coding da Vinci Culture Hackathon

One of my cases is the Coding da Vinci (CdV) cultural data hackathon in Germany. The word hackathon is a combination of “hacking” and “marathon” and describes a time-limited event in which people meet to find creative solutions to a challenge.

CdV is an event series, which was developed by a group of people working in open GLAM (short for galleries, libraries, archives, museums) organisations and their aim was to create a format which would illustrate how open cultural heritage data could be reused. During the CdV West hackathon (October-December 2019) I did participant observation and conducted interviews with the participants afterwards.

Remix Workshop at the Museum Europäischer Kulturen

A second case on which I am building my research is the Remix Workshop at the Museum of European Cultures (MEK) in Berlin. Together with another POEM fellow, Susanne Boersma, I developed and organised the workshop during my POEM secondment at the MEK (November-March 2020). We were curious to try out other ways of using digital objects – in this case, object images – without having programming skills, so we decided to use collage making and stop-motion animation as creative techniques instead. Here, we invited participant to our workshop at the museum and conducted interviews with them afterwards.

At the moment, I am in the phase of transcribing, coding and analysing my research data with the software MaxQDA. Being in the middle of the process, I will only present a few examples to give an idea of the variety of uses I found.

How did participants in both settings use objects?

The first example I chose is a quote from a participant of the hackathon who explained the interaction with cultural heritage data in the following way:

„At the same time you can experience these data sensually again and again: you look at them, you work with the pictures or with the sounds. On the other hand, you have this constructive and the creative effect – constructive in the sense of programming, creative in the sense of interface design and how you put this data into new contexts.”

This participant chose sounds of industrial machines (e.g. a gas drilling machine) because they offered the highest data quality and sparked an idea for them. What they did with this data is described as a sensory perception, a repetitive process of almost diving into these sounds. This approach emphasises the materiality of the digital as well as the personal enjoyment of recontextualising this rich material with creative and constructive tools.

The second example is from the remix workshop and explains how the digital technique we used in the workshop allowed to add a personal interpretation to the object.

“[we] had the time and the motivation and the possibility to take the museum object out of context and then put it back and then with that act still create a little bit like an own museum, like a mirror of the same object but a more personal one.”

This participant chose images of the paper theatre, because they were involved in a theatre group at the time of the workshop and it reminded them of playing puppet theatre as a child. The object offered a starting point for them to think about multiple meanings and current questions. The digital image of the object made it possible for them to literally reflect – acting like a mirror – their own thoughts, and with the techniques of collage making and stop-motion, to add their personal interpretation.

Some hackathon participants approached cultural heritage data mostly in a practical sense, stating: “[…] we just see how we can handle it with the technologies we use.”, while others challenged themselves to figure out what can be learned from it:

“[…] the question is always what to do with this old data. You don’t just look at them because they’re 100 years old, you look at them to see what was discussed 100 years ago and what can you take from it.”

Concluding for now…

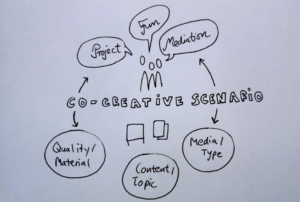

As an interim conclusion I tried to visualise (Figure 1) the key elements which shape the use of digital objects in co-creative processes.

The co-creative process is initiating and framing the use of objects: in terms of format, length, participants. Within this process the concept of affordances-in-practice as introduced by Elisabetta Costa (2018) and further developed by Christoph Bareither (2019), is a helpful lens because it emphasises the middle ground between technological determinism and social constructivism and pays attention to the relational character of user practices. Affordances-in-practice are defined by situational context, embodied knowledge of users and the potential of digital media.

The examples from both cases make this relational character very visible – we can say for now that objects build the base and starting point in both co-creative processes but the way that they function in each case varies considerably: they are seen as medium and type of media, content or topic, or in their qualitative and material aspects. On the other side, these perspectives depend on the people who joined the hackathon and the workshop. Participants’ embodied knowledge, their background as well as their intentions and motivations influenced very much what they used objects for – whether they used the objects to create a project for their professional portfolio, were hoping to convey an educational message, or were just enjoying the creative activity.

Both the hackathon and the remix workshop formats were inspired by user practices of hacking and remixing. These practices are not entirely new, but they have been amplified by digital technologies and what Felix Stalder (2016) calls the ‘digital condition’ – the digital culture. So, I would say it is not only the technology but the digital condition which offers new possibilities for participatory projects. In this vein, remixing and hacking offer an ‘area of curiosity’ (Lindström & Ståhl, 2016) which heritage institutions can use to invite people and to enable co-creation with digital objects.

In order to unleash the full potential of digital collections however, memory institutions need to understand that co-creation is not the cherry on top but the base of their digitisation projects. Co-creation with digital objects is a great way to explore multiple meanings of these objects not only theoretically but in a tangible way of prototyping: to manifest the shared knowledge and multiple reinterpretations and to test the quality of data. In that way, co-creation forms an essential part of a healthy digital content life-cycle.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank the hackathon and workshop participants for sharing their time and creativity with me. I am also grateful for the support I received from Susanne Boersma and all staff members of the Museum of European Cultures during my secondment. And I would like to thank the Coding da Vinci organisers for supporting my research.

Franziska Mucha is a POEM Fellow based at the University of Glasgow. Her research interests are co-creation and crowdsourcing of cultural heritage, participatory museum practices, and the role of memory institutions in the digital condition.

Twitter: @FranziskaMucha

Email: Franziska.Mucha@glasgow.ac.uk

References

Bareither, C. (2019). Doing Emotion through Digital Media: An Ethnographic Perspective on Media Practices and Emotional Affordances. Ethnologia Europaea, 49(1). https://doi.org/10.16995/ee.822

Cameron, F. & Mengler, S.a (2009). Complexity, Transdisciplinarity and Museum Collections Documentation: Emergent Metaphors for a Complex World. Journal of Material Culture, 14(2), 189–218. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359183509103061

Costa, E. (2018). Affordances-in-practice: an ethnographic critique of social media logic and context collapse. New Media & Society, 20(10), 3641–3656. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444818756290

Dahlgren, P. & Hermes, J. (2015). The Democratic Horizons of the Museum: Citizenship and Culture. In A. Witcomb & K. Message (Hg.), The International Handbooks of Museum Studies: Museum Theory (S. 117–138). John Wiley & Sons Australia, Ltd. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118829059.wbihms107

Gesser, S., Gorgus, N. & Jannelli, A. (Hg.). (2020). Edition Museum: Bd. 31. Das subjektive Museum: Partizipative Museumsarbeit zwischen Individualismus und gesellschaftlicher Relevanz (1. Aufl.). transcript. http://www.transcript-verlag.de/978-3-8376-4286-5

Kallinikos, J., Aaltonen, A. & Marton, A. (2010). A theory of digital objects. first monday. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.5210/fm.v15i6.3033

Lindström, K. & Ståhl, Å. (2016). Politics of Inviting: Co-Articulations of Issues in Designerly Public Engagement. In R. C. Smith, K. T. Vangkilde, M. G. Kjaersgaard, T. Otto, J. Halse & T. Binder (Hg.), Design anthropological futures: Exploring emergence, intervention and formation (S. 183–197). Bloomsbury Academic an imprint of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc.

Müller, K. (2019). Vom Nutzen digitalisierter Sammlungen. Museumskunde(84), 12–17.

Nauta, G. J., van den Heuveland, W. & Teunisse, S. (2017). Europeana DSI 2–Access to Digital Resources of European Heritage: D4.4.Report on ENUMERATE Core Survey 4. DEN Foundation. https://pro.europeana.eu/files/Europeana_Professional/Projects/Project_list/ENUMERATE/deliverables/DSI-2_Deliverable%20D4.4_Europeana_Report%20on%20ENUMERATE%20Core%20Survey%204.pdf#page=34

NEMO. (June 2020). Digitisation and IPR in European Museums: Final Report. Network of European Museum Organisations. https://www.ne-mo.org/fileadmin/Dateien/public/Publications/NEMO_Final_Report_Digitisation_and_IPR_in_European_Museums_WG_07.2020.pdf

Owens, T. (2013). Digital Cultural Heritage and the Crowd. Curator: The Museum Journal, 56(1), 121–130. https://doi.org/10.1111/cura.12012

Prahalad, C. K. & Ramaswamy, V. (2004). Co-creation experiences: The next practice in value creation. Journal of Interactive Marketing, 18(3), 5–14. https://doi.org/10.1002/dir.20015

Sandell, R., McSweeney, K. & Kavanagh, J. (2016). A Reflection on Participation. In K. McSweeney & J. Kavanagh (Hg.), Museum participation: new directions for audience collaboration (S. 578–601). Museums Etc.

Sanders, E. B.-N. & Stappers, P. J. (2008). Co-creation and the new landscapes of design. CoDesign, 4(1), 5–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/15710880701875068

Simon, N. (2010). The participatory museum. Museum 2.0.

Srinivasan, R., Becvar, K. M., Boast, R. & Enote, J. (2010). Diverse Knowledges and Contact Zones within the Digital Museum. Science, Technology, & Human Values, 35(5), 735–768. https://doi.org/10.1177/0162243909357755

Terras, M. (2015). So you want to reuse digital heritage content in a creative context? Good luck with that. Art Libraries Journal, 40(4), 33–37. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0307472200020502

Valeonti, F., Terras, M. & Hudson-Smith, A. (2019). How open is OpenGLAM? Identifying barriers to commercial and non-commercial reuse of digitised art images. Journal of Documentation, 76(1), 1–26. https://doi.org/10.1108/JD-06-2019-0109