Friedemann Yi-Neumann (University of Göttingen)

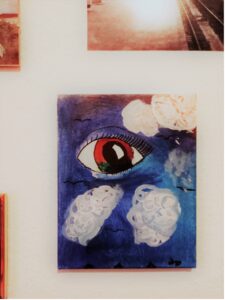

“Let’s make it!” canvas in the author’s home. (Picture by author, 2021)

When I started my research at the Department of Social and Cultural Anthropology, University of Göttingen, in 2018 on the “On the Materiality of (Forced) Migration Project” (MatMig) I immediately was confronted with the role of museum objects in my ethnographic research in the Friedland Transit camp and beyond. The project is a cooperation between the exhibition agency “Die Exponauten” and “Museum Friedland”. In the conversations my colleague Samah Al-Jundi Pfaff and I had in the camp, we collected the stories of people who had escaped war and violence, and sometimes, when people made an offer to the museum, we also collected some personal items brought along.

As a material culture anthropologist, I am used to understanding and describing human-thing relations and interactions; what things mean for people, how they use them, and how things and humans transform (each other) over time during migrations. Here things are not only objects but also means of research; they are a part of social relations and, due to their affective character, can help to explore unconscious and unspoken aspects ‘beyond words’ (Auslander, 2005).

As a result of collaborating with a museum, we added the collection of things to our research objectives. Friedland Museum is experienced in collecting items of displaced persons, German soldiers returning from war captivity, ‘late repatriates’ (“immigrants of German descent” from the former Soviet Union), so-called ‘Boat People’ fleeing Vietnam, and GDR escapees who were accommodated in the transit camp and conducting numerous biographical interviews with the possessors or their descendants.

No Things

For different reasons, the MatMig project, which focused on current refugee reception dwellers in that place, was ‘successful’ in terms of its ethnographical and biographical accounts. However, the whole endeavor was rather modest in terms of collecting material objects for the museum depot. The reasons for this were manifold:

1. In the context of forced migration and especially illegalized migrations, having and keeping private things often is a privilege in the face often severe and multiple dispossessions. Frequently, refugee arrivers who had escaped war and experienced years in precarity did not possess much. As a result, some had to learn to live without personal things.

2. Even if people had saved weighty personal objects, sometimes they were emotionally highly dependent on them; thus, giving these things away was out of question. Possessing the freedom to hand over momentous belongings to a museum requires a certain degree of personal certitude and emotional interdependency from the items many arrivers did not possess.

3. Despite the information we provided, people gave things to the museum and had high hopes of having their objects on display and not in storage. In one case, disenchanted donators demanded the return a self-made print of a martyred friend, as the desire for having it presented in a display did not correspond with the museum operation modes.

Remnants

Anthropologists have vividly described the power asymmetries, irritations and difficulties of collecting material culture in refugee camps (see e. g., Sandra Dudley, 2021 on the displaced Karenni community). My colleagues and I were not looking for things to represent different communities. Instead, we were interested in learning which material objects do (not) matter for people, emotionally, biographically, practically and by this, comprehending their thoughts and relations to other people and things.

Usually, the belongings given to us were transported in backpacks; people who had the privilege to enter Europe by plane carried them in a suitcase. Often they are remnants of a larger setting of what was left behind. Different passage points on flight trajectories, like challenging environments, militarized borders but also means of transport claim their tribute only allowing for minimal luggage and thus force people to leave things behind (in stages).

More than once, the conversation situation in Friedland was the first occasion for people in a long time to reflect on what they had carried with them and how they saw it. The things were usually crammed, sometimes even broken to make them fit into the baggage.

When someone decided to hand over a personal item to the museum, it usually moved to our, the ethnographers informal storage.These things were also used as a means of re-presencing during ethnographic analysis (see Marta Vilar Rosales, 2020). Eventually, they were handed to the museum archive, inventoried, and from then on professionally handled and stored by conservators, and hopefully staged someday by curators. Classically, objects are then afforded new values by shifting them from the fields of social practice and circulation to the ones of storage and representation.

Privileging objects in terms of preserving and displaying has been a key practice in traditional museums. Nuala Morse (2021) offers a critique in this regard and demands that museums be turned into spaces of social care instead of places that primarily care about objects. Morse and other participatory museum scholars also have objects in mind when they reflect on participatory practices. I state, however, that material objects in museums are a crux for participatory approaches that is insufficiently reflected.

Joint Creation

The accessibility to things in museums is usually a constraint; objects are dedicated to experts, with very few exceptions, to avoid damage by improper handling or storage. Museum objects require an institutional setting that guarantees their integrity, making exhibitions expensive and limiting them to classical museum spaces. The border anthropologist Jason de Leòn and the Undocumented Migration Project (UMP) team developed a curatorial answer to this problem. Working on the US-Mexican border regime and its fatalities, aware of the limitations of their previous more or less ‘classic’ exhibition endeavors, the UMP originated a pop-up exhibition called Hostile Terrain 94 being both political intervention and an act of commemoration shown in 150 places around the globe. In terms of exhibits, the project is remarkable, since by filling in toe tags of people who lost their lives on their way to the US and pinning them on a giant map of the Sonoran Desert, the participating groups create ‘their specific objects’. In each place, the handwritten toe tags reflect joint efforts to write down the names of the deceased commemorated by this and to create an exchange on the humanitarian border crisis.

This effort of joint creation made me think of materials piled up in Samah’s office in Friedland Museum, which I did not initially consider to be museum objects: paintings. I had the privilege to join the workshops of Samah called “Let’s make it!”. Samah has an extraordinary capability of bringing people from different backgrounds together: (former) transit camp dwellers, artists, activists, and people interested in learning and exchange.

These workshops turn museums into vibrant places, where people engage in music, dancing, and storytelling, exchanging over the flight from war, migration, and arrival, visually expressed in paintings of all kinds. Some of these hundreds of jointly created art pieces are now shown in an exhibition entitled “I FEEL”(online / and on-site).

I claim that workshops like these provide answers to the difficulties around museum objects in the context of forced migration and to the structural constraints and obstacles exhibits in museums bring with them. Acknowledging that museums enable but also necessarily limit access to things and thus participatory engagements, I propose an understanding of museums as workshops. Rather than merely keeping and staging, museums can not only enable contact but can become a zone of collaborative production, production, not only of alternative forms of knowledge but also of various kinds of objects.

Productive Links

These crafted things reflect not only skills and perspectives but also the material conditions of their joint creation. They are not only ‘objects of refugees’ or ‘of migration’ but of collaboration. As in every other production place, it is necessary to shape conditions as equally and democratically as possible. The new things resulting from bringing people together, learning from each other, and thinking out of the box are continuously made and in many places are already there. This essay is a call to recognize these items as valuable things and also as exhibits. During “Let’s make it!” things were not necessarily created for the museum display, many did find their ways into homes and connected people and places. Such joint productive collaborations can enrich museums, their inter-relationships, and the networks which reach beyond them, but they need space and cultivation to flourish.

Bio

Friedemann Yi-Neumann is a research fellow on the migration exhibition project MOVING THINGS (University of Göttingen). Previously, he was a scientific coordinator at the Institute of Social and Cultural Anthropology at the University of Göttingen in the BMBF research project ‘On the materiality of (forced) migration’. In addition, he held a position in the Mobile Worlds research project (Goethe University Frankfurt). Yi-Neumann examines the relevance of material culture in the forced migration context. His main research interests are material culture, forced migration and post-migration, asylum reception, dispossessions, homes, everyday life, phenomenology and museums.

References:

Auslander, L. (2005). “Beyond Words.” The American Historical Review 110(4): 1015-1045.

Dudley, S. H. (2021). Displaced Things in Museums and Beyond. Loss, Liminality and Hopeful Encounters. London, Routledge.

Rosales, M. V. (2020). On the Materiality of Forced Migration: Methods. Materializing the Transient: Ethnographies and Museums in the Study of (Forced) Migration. A. F. Lauser, Antonie, F. Yi-Neumann and P. J. Bräunlein. Göttingen, BMBF Research Project “On the Materiality of Forced Migration”.