Reviewed by Quoc-Tan Tran, with contributions from Susanne Boersma, Franziska Mucha, and Myrto Theocharidou

The POEM closing conference was held as a hybrid event on March 4th and 5th, 2022. The physical conference venue was located at the University of Hamburg (Germany). Several dozens of people from the United States, Namibia, and other parts of Europe were participating via Zoom. The conference, themed “Futures of Participatory Memory Work,” aims to foster discussion about new approaches to open, participatory, and socially inclusive memory work in today’s digital media environments. Throughout the conference’s various activities, three groups of sub-themes and questions were highlighted.

- How do we enable memories that belong to differently situated communities and life experiences to become parts of remembering, but also parts of new types of dialogues in institutions?

- How do we envision the plural paths of world-making, with multiple voices and worlds and with plural futures, and in doing so, create new types of socially inclusive living spaces or scenarios?

- What are the opportunities for researching alternative memory practices and imaginations?

The first day of the closing conference began with a keynote address by Areti Galani, which was streamed live via Zoom. It then moved on to a hybrid discussion of the output of the three POEM work packages.

Keynote by Areti Galani

The future has recently become a subject of growing interest in museums, particularly in exhibitions ranging from expos to more recent showcases in science, design, and immersive art museums. Galani reminded the audience that the future and future technologies had captured the imaginations of curators and audiences alike. Recently visiting the exhibition “Before Yesterday We Could Fly: An Afrofuturist Period Room” at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, she said this is one of the most recent attempts to not only display the future but also to practice a form of featuring through speculation. There is no doubt that notions of the future underpin all aspects of heritage and memory work. These ideas of the future influence not only the institutional but also personal decisions on how to value specific aspects of the future, to include or exclude them from our personal and collective narratives, or align them with our vision for the future of these narratives and their future audiences.

Galani’s work is based on museum professionals and inherited institutional memory practices, rather than the perspectives of communities. There is a reflexive relationship between past and future through present and the facilitation of memory work. In the talk, she makes an assumption that the future is not out there waiting to be predicted. Researchers, technology designers, and analysts, according to her, are currently and continuously producing futures in the making, including futures in which specific aspects of our heritage and memory will not exist. Furthermore, the ability to imagine the present or future may be unevenly distributed, and this unevenness may or may not follow the well-known patterns of inequality present in societies. Recognizing this unevenness, according to Galani, is critical for any future in work that requires imagination.

Galani affirmed, “we were keen to explore participatory speculative design” rather than the more typical speculative design approach of presenting speculations to the public in an exhibition or gallery space. Including a participatory element, she reasoned, would allow researchers to explore how futurescaping can help them envision alternative heritage futures through hands-on experience and the mobilization of creative labor, as well as create spaces for dialogue.

Galani’s talk, streamed via Zoom, is available here.

Synthesis Day 1: Work Packages’ output and POEM’s efforts in futuring

Prof Rachel Smith of Aarhus University in Denmark remarked that she and her colleague Heike Winschiers-Theophilus1 had worked on participatory design, design, and quality technology for many years. Several of the themes they have encountered through the work packages are pervasive throughout the projects, for example, the concept of futures and futuring as a lens through which to view memory practices, as well as approaches to developing participatory methodologies in research and practice. Rachel’s most pertinent question is: So, how do we shape the future? Or, to put it another way, how does shaping the future through engaging differently with the past and the present allow us to imagine new possible futures?

“… we also can ask then, if we start to think about or we use futuring, as an approach to thinking about heritage, what does the past and the present experiences then mean to us? What kind of status do they get as an object of research, when we start futuring memory practices, and who is responsible for the future, or who is responsible for the futuring, or the documentation of what we can imagine as possible futures?” (Rachel Smith at POEM Closing Conference)

For Rachel, there are two potential threads of discussion in futuring. Firstly, the theme of temporalities. The three Work Packages of the POEM project have resulted in “extending the temporalities, but in a multiplicity of ways,” observed Rachel. The public, GLAM practitioners, and researchers can watch and reflect on the thirteen short videos created by POEM fellows2, and might ask the question: What kind of lens should we use to view the future? And are we really interested in projecting new futures? Or, are we creating and co-creating our present through thinking about the past and the future, as well as the relations between different temporalities. A fruitful outcome of the thirteen individual research projects is a renewed emphasis on the present, and on how we construct the present through our engagement with the past and future, using the present as a source or the time for doing so. The second theme that is relevant to futuring, for Rachel, is pluralistic forms of knowledge and knowledge production, which is critical in terms of how individuals (and institutions) create inclusive futures or precedents, i.e., ways of creating memories that belong to different very particular and situated communities and life experiences.

Prof Heike Winschiers-Theophilus joined the discussion, noting that the most pressing question at the moment is probably: how is this research affecting the real world, particularly heritage practices and heritage management? What happens after the POEM fellows have worked with institutions and participants on the topic of future envisioning and sustainability as a form of intervention? Heike suggested that the difficulties in envisioning futures and disseminating the results of research projects lie in making necessary attempts to reshape power structures, bringing in new skill sets for memory workers. According to Heike, new power structures are emerging and will emerge as a result of technology and there are always people who understand technology, just as there were in the past, people who understood how to write history. They are those who were able to create narratives and continue to be able to do so. “Perhaps the youth will be able to write the narratives, but what does that mean for the skill sets of those involved in memory work?” she asks.

From Heike’s perspective as a Namibian researcher who has long worked on issues of participation and inclusion, there is a debate about the extent to which indigenous people are involved in memory-making projects initiated by memory institutions, and in the curation of cultural heritage. With the advancement of technology, digital tools, and platforms, she observes, we are once again confronted with the same power structures. People have expressed concern about how Wikipedia, for example, excludes the perspectives of indigenous people by restraining oral citations. Heike lauded POEM’s ongoing efforts to foster research in/within/with the participatory memory spaces and to contribute to exploring hidden layers of participatory futuring. She asked: What does participation actually mean, and if we are going in this futurescaping direction, could we imagine alternative modes of participation? Heike wishes to leave audiences with such thoughts.

Speed-dating

On the conference’s second day, both online and offline participants took part in a ‘speed-dating’ session. This activity took place exclusively as an online session. Using the Zoom platform, conference participants were assigned to different break-out rooms (of 2-3 people each) to discuss questions, comments and issues raised by the pre-recorded presentations and discussion sessions on the first day of the conference. Participants were given ten minutes of dating before being re-assigned to a new break-out room. The process was repeated four times and the major points of discussion from each session were compiled into a padlet document to serve as the foundation for the following activity: co-creative session.

The speed-dating session is held via Zoom and Padlet, with both on-site and online participants. Photo by Myrto Theocharidou

Co-Creative Session

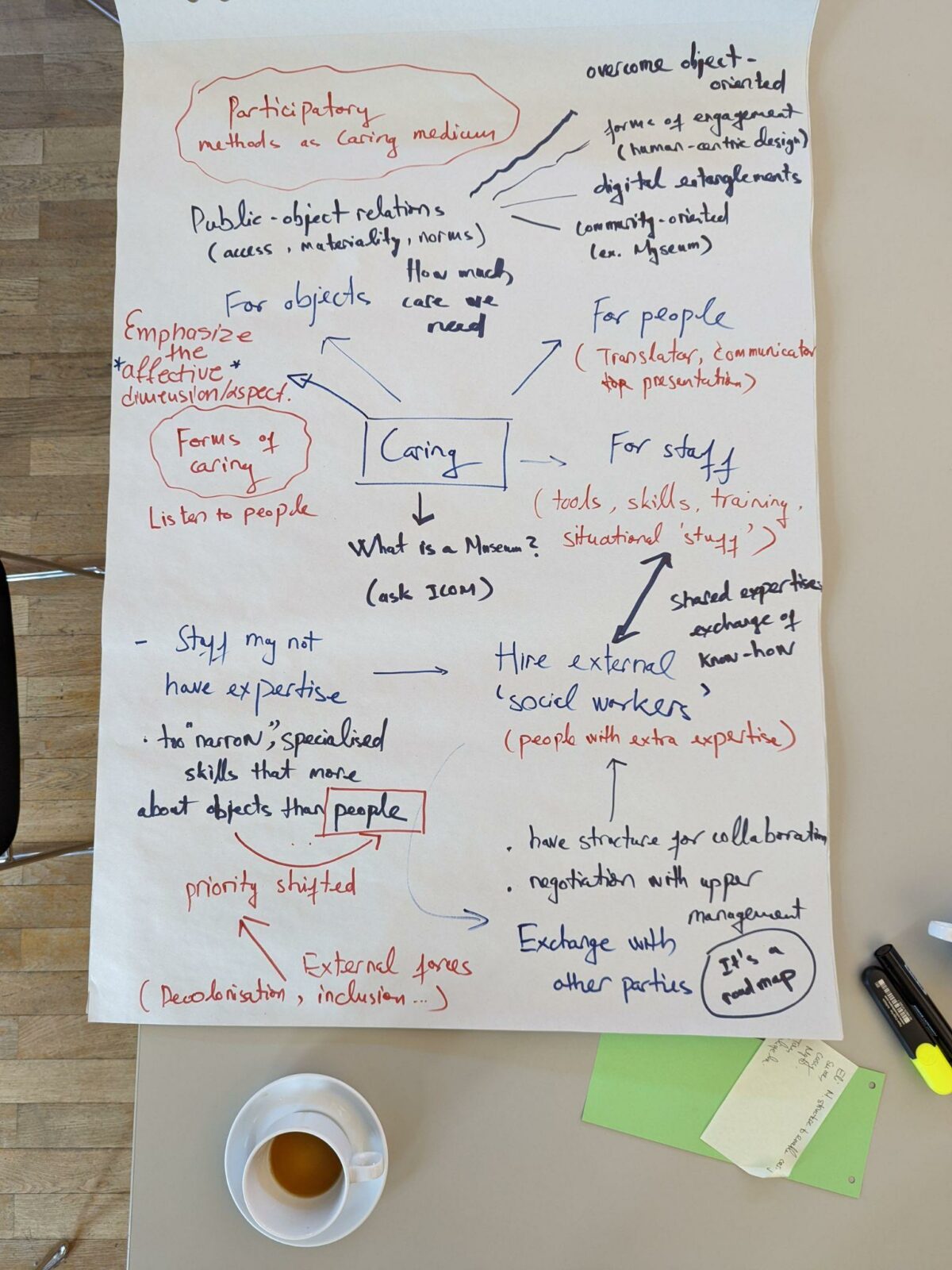

The co-creative session built on the speed-dating session. The themes that had been voted for most were combined to divide the attendees into groups to focus on the following points:

- Rethinking museum structures to enable a practice of care

- Positioning as a researcher/practitioner/activist

- The friction between safe spaces and unsafe spaces (and for whom)

- Futuring grounded in the everyday

Following their work in small groups, participants reconvened in the main room to share their ideas. The groups presented what had come up and how it could be visualized, moderated by Franziska Mucha and Susanne Boersma. Through the use of GIFs, magnetic balls, rubix cubes, and schematic drawings, the presentations took us from very practical museum work to the possibilities of connecting on an equal footing with participants, from the characteristics of a safe space to considering the two approaches to futuring.

Visual output from Group 1: “Rethinking museum structures to enable a practice of care”. Photo by Quoc-Tan Tran

POEM Toolbox session

This session showcased all of the tools developed by the POEM fellows.3 Elina Moraitopoulou shared an engaging reflection on her tool “School Memory Work – Prompt Cards” and the process of developing it through her work with school children:

This tool4 is essentially something that emerged from a focus group, work that I did with a group of approximately nine students and one of their teachers. We tried to work around questions that facilitate the elicitation of memories that relate to school experiences, and we tried to adopt it to a school’s environment. And then, we worked with different prompts to elicit feelings and we identified the different parameters that would make this process deeper – questions that pertain to how different memories felt. The focus of this tool was on the different senses that engage us to the different memories that we hold, all the different places where they took place, the people who were involved, the different timings, etc. I have uploaded the prompt cards. What is really interesting is that in the literature, such approaches have never been used, or at least to my knowledge, with children, death, certainly not in educational contexts, and not outside a certain therapy setting, or memories that relate to certain traumas. I would want to develop further what I call a method and a space. So not everything is in the tool yet. It’s a work under progress. The idea is to create a space where not only young people, but also older people from the educational community can gather together and exchange their memories of schooling that matter to them. And through that process, at least, it’s in particular the affective dimensions that related to specific school experiences that they want to bring forward to the future. And I think that at least from what I saw from the work that I did on the small scale, this is a very fruitful way to engage different generational perspective, and also, when it comes to discussing what needs changing in education, the question of how education futures can be envisioned.

POEM Book Series

Prof Gertraud Koch, the POEM network’s coordinator, introduced the book series “Participatory Memory Practices: Digital Media, Design, Futures” on behalf of the editors. To be published by Routledge, the series will look at the mediatized nature of memory making, as well as the challenges and potential benefits that emerge from participatory memory making. The series as a whole, according to Gertraud, aims to provide knowledge and ideas for “creating socially inclusive, sustainable and future-oriented memory practices.” In particular, it aims to publish forward-looking, empirically grounded research monographs and edited collections that will be able to “set the multidisciplinary research agenda for studying heritage in contemporary digital media as an element and a driver of cultural and social change.”

For good things to come: POEM community of practice

Prof Ton Otto of Aarhus University concluded the second day of the conference by discussing the potential for establishing and expanding the POEM “community of practice.” Ton said that he experienced a similar time in his career when he was asked to establish a community of practice, owing to a growing interest in a field that was not yet organized in Europe, namely oceanic study, or more precisely, interdisciplinary Pacific Studies. Ton asserts that when considering what a community of practice is, it should be something that needs to be practiced: It is an activity, but one that requires structure and infrastructure. It requires some individuals to act and organize that action in such a way that it becomes sustainable.

The POEM project began as an Innovative Training Network, which, according to the Horizon-2020 framework, “supports competitively selected joint research training and/or doctoral programmes, implemented by partnerships of universities, research institutions, research infrastructures, businesses, SMEs, and other socio-economic actors from different countries across Europe and beyond.”5 Ton believed that it was an excellent start, as it allowed all the fellows and supervisors to get to know one another and gain experience with various forms of exchange. For Ton, the book series can serve as a “flagship” for such a community to evolve, that is “visible as a deductive way of getting all kinds of research out in a more lasting form.”

For sustaining a community of practice, Ton suggested, even though the primary focus is on activity, infrastructure and a publication outlet are also critical. He viewed that a community of practice should function as both a physical and digital platform. He referred to PECE (Platform for Experimental Collaborative Ethnography), a promising collaborative ethnography platform developed by the Center for Ethnography at UC Irvine, as an inspiring example. Such a platform is crucial for the development of a community of practice because it serves as the organizing motivation and structure, just as Ton and his colleagues did 30 years ago when they organized their first conference:

We did it [building the network] by contacting other people because I believe this group is fantastic and will continue in some form or another. Also informally, because friendships has started supervisory relationships and then started job networks, these tight relationships will continue to exist after the POEM network. I believe that the dream of many of us is that it grows even larger and sustains itself: how to get other people in. And that could be by organizing.

Aspiring to establish a community of practice, for Ton, entails assembling a group of individuals who will view this emerging field as “theirs, their thing, their occupation,” and will want to use it in the same way and as much as they would use the existing universities and museums, because “they’re great places,” Ton said.

At the conclusion of the conference, POEM fellows and supervisors formed the letter “P” with their hands. The letter, of course, refers to POEM, but could also mean People. And Participation. And Practice.

POEM fellows and supervisors in front of the University of Hamburg’s main building.

Notes

- Professor at Namibia’s University of Technology, who has collaborated closely with the Aarhus team on numerous projects and contributed significant ideas to the POEM project throughout. Her public lecture at POEM Knowledge Hub 4 is available at: https://www.poem-horizon.eu/heike-winschiers-theophilus-where-the-past-is-still-present-co-designing-digital-technologies-for-contemporary-multi-cultural-namibia/

- All videos from POEM fellows are available at: https://www.poem-horizon.eu/futures-of-participatory-memory-work/

- All POEM tools are accessible at https://www.poem-horizon.eu/news/

- Available at https://www.poem-horizon.eu/school-memory-work/

- https://cordis.europa.eu/programme/id/H2020_MSCA-ITN-2020